The Mystery of a Haunted Railway Station

Written by Hubert Kahl (Translated from the German text into English by Dolores Schebendach)

Canfranc/Pyrenees – The train journey is almost uncanny. Low-lying clouds cover the mountain sammits of the Pyrenees. With difficulty the train makes it’s way up the slopes, through valleys and tunnels. Almost empty it clatters over the old railway tracks. On the last section, from Saragossa to Canfranc in Northern Spain, a single passenger goes astray in the “train”. In actual fact, the Regional Express only consists of one wagon!

The rail terminus looks ghostly in the dark. Only a few lights lend the enormous station with a bit of eerie light. The rain drips through the rotten roof and the entrances to the building are closed or barricaded with wire-netting. The traveller is given a picture of desolation and neglect when looking through the broken windows. Only ¡ruins and rubble remain of the old ticket counters. Fragments of fallen ornaments and other objects lie scattered around.

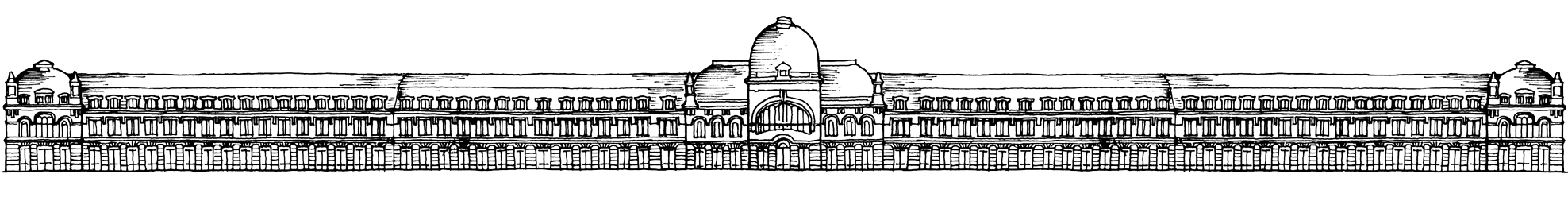

In earlier times this station – situated in a Spanish border town called Canfranc – could compete with any other big city station. It was once described as “bigger than the Titanic” on tourist posters. Why is such a big railway station so deserted and neglected today? The small town was 600 meters long and only had 550 inhabitants!

At the end of the 19th Century, Spain and France agreed to build a railway line through the moutains. River courses were diverted for this purpose, embankments for the rail-tracks were made and dozens of tunnels dug. The railway line was completed in 1928. The new international border town railway station in Canfranc was celebrated with hymus and fanfares. It was opened by the Spanish King Alphonso XIII and the French State President Gaston Doumergue.

But this modern, magnificent building was only• allowed to experience a short period of splendour. It’s decline and ruin began during the turbulent Second World War. At that time, the Canfranc long-distance trains travelled to Paris, Valencia, Madrid and Lisbon. The trains were furnished in an Orient Express style and during the sixties, Canfranc station was even used as a site for the filming of Doctor Shiwago. Today only two rail-cars, which travel from Saragossa, stop here.

Many gruesome and strange events took place during the time of the gradual ruin of the station. One of these things was discovered by Jonathan Diaz. Diaz was employed as a bus-driver for a bus-line wich travelled to and from Canfranc and the French town of Oloron-Saint Marie. Whilst waiting for the scheduled departure of his bus, one gray November morning almost two years ago, he strolled over the station railway lines which were at that time overgrown with weeds and shrubs. Suddenly he came ≥across a pile of old war-time castoms’ papers. „Stamp collectors had probably thrown the papers away after rummaging throngh the envelopes“, the driver reports. Diaz picked up a handful of the scattered papers and put them in his jacket pocket.

When he arrived home that night, he looked at the papers more closely. His eyes fell on the words “Three Tons of Gold Bars”. At once he realised that his discovery could be of great importance. The bus-driver, who was the son of a Spanish emigrant, had heard rumours in Canfranc that the Hitler Regime had smuggled robbed gold over the border station to Spain and Portugal. The same night he went back to the place where he had found the old papers. He collected them and put them in a plastic bag.

The forty-year old Diaz had actually found “a piece of history”. He carefully spread the documents out in front of him. The papers were yellow with age, partly dilapidated and looked as though they had ∆been nibbled at by rats or insects. The papers Diaz had found were only copies, but they were certainly genuine. All goods which had passed through Customs had been registered. The originals were never found and to this day, no-one knows what has happened to them.

These documents proved that during June 1942 and December 1943, 86.6 tons of gold had passed over the border in Canfranc – 74.5 tons landed in Portagal and 12.1 in Spain. The Nazi Regime had taken this precious metal from national banks in European cities. This gold – together with gold-teeth, rings, watches etc. which had been taken from the dead Jewish people was melted and became the so-called “plundered gold”.

This gold reached the Iberian Peninsula via Switzerland. In exchange, the Spanish and Portuguese gsve Nazi Germany “Wolfram” ore which was badly needed at that time for the production of military weapons.

This discovery was indeed a sensation. Historians licked their fingers when⁄ they heard about Diaz’ find. Until that time no-one had known of the gold transport which has passed through Canfranc. No mention of the little town in the Pyrenees was ever made in any other document or assessment as to the whereabouts of the plundered gold. The papers which Disz had found also proved that Spain and Portugal had reccived much more of this gold than had been estimated.

Diaz thought that this discovery should have actually caused a scandal. After all, the papers proved that the two dictators, Francisco Franco in Spain and Antonio Oliveira Saiazar in Portugal, had collaborated more closely with the Nazi Regime as far as the gold transactions were concerned.

Surprisingly enough this discovery had no reaction whatsoever, not even on the International Jewish Organisations. It seems as though there was a very good reason for this silence, as not only gold and “Wolfram” ore were transported throngh Canfranc, the little town had other secrets as well. Accordin»g to Ramon J. Campo it had saved the lives of many Jewish people and anti-Nazi resistance fighters.

Campo, the editor of the newspaper “Aragon Herald”, was a quiet person. Very little could disturb him but his eyes lit up whenever Canfranc was mentioned in conversation. Ever since he had met Diaz, the bus-driver, the history of the railway station in Canfranc had fascinated him. He spoke to all the people in the little town and wrote a series of articles about the old station. He also published a book called “The Gold of Canfranc”. He wrote about the railway line through Canfranc which had been the door to freedom for many Jewish people and others who had been chased and hunted by the Nazi Regime.

Spain, at that time under Franco’s dictatorship, was faced with a divided opinion as far as the fugitives were concerned. On the one side, Franco made it possible for the Jews to flee via Spain to North Africa or to Lisbon and from there to America. Franco ha«d allowed this as his conntry was dependent upon Britain and America to deliver Spain oil. On the other hand, Franco was indebted to the Nazi Regime because Hitler had supported him during the Civil War (1936 to 1939). In order not to annoy Hitler, Franco made sure that the stream of fugitives did not increase too much.

Campo believes that some type agreement exists between Spain and the Jewish World Congress (WJC). The WJC has probably not demanded that the question of the plundered gold be investigated in detail because Franco had opened the door to freedom for so many Jewish people.

The bus-driver’s discovery would never have been made public if the book had not been published. Campo also found a certain David Sanchez who had worked in the loading zone

at the station at that time. He had loaded crates of gold. Just before he died, at the age of eighty-eight, Sanchez said that it wouldn’t have made any difference to him if he had had to load gold or• tins of sardines, but he would have actually preferred sardines as at least they were eatable. He was very often on the edge of starvation.

In 1942, the Swastika was hoisted over the station. Canfranc became, as Campo said, a stratigic point. The south of France was occupied by the German armed forces and they were making their way towards Canfranc, even although this town was situated eight kilometers further from the border and Spain wasn’t involved in the war. When the German troops marched into Spain they made use of the fact that the town and the station belonged to Spain and France. Spanish police and soldiers as well as German armed troops patrolled the streets of Canfranc.

The town became an ideal place for secret agents. One of them, Albert Le Lay, Chief of the French Customs, acquired the nickname „King of Canfranc“. He acted as contact man for the French resistance movement and the Allied Forces. He providäed the Americans and the British, through their Embassys in Madrid, with information which the Allies needed for the landing in the Normandy. His activities were discovered by the Gestapo in 1943, but „Monsieur Albert“ managed to flee to Algeria.

When Hitler’s defeat became obvious, hundreds of German soldiers flew from the Allied Forces to Canfranc. Ironically enongh, they chose the same route which was taken by the Jewish fugitives. Santiago Marraco, who had witnessed these activities at that time, remembers that „the German soldiers came in groups of fifteen or twenty men on foot from France, through the railway tunnel. I saw them come regularly in batches. Some of them were wounded. Others seemed lifeless, confused or deranged“.

The war ended and with it the glory and splendour of the station came to an end. Franco closed the rsilway line for many years. He was afraid that Spanish Partis•ans from France might move to Canfranc. In 1970 the railway line was closed for ever: While travelling on French soil, the brakes of a goods-train failed and the wagons, together with the bridge, crashed into a small river. This occurence was very welcome to the French, as it provided a very good reason to finally close the railway line.

„Why hasn’t anyone made a film about the history of Canfranc,“ asked the young Mayor, Victor Lopez. He had often tried to get the railway line into operation again, but he was unsuccessful. „It is such a pity that the station has fallen into ruins. It could be turned into a building with a railway station, hotel and museum“.

The mayor referred to an agreement between Paris and Madrid that the railway would be re-opened as from 2006. But there were doubts about this as the condition of the railway tracks on the French side were very bad and also, the tracks were overgrown with bushes a§nd mulberry shrubs, and railway bridges had been demolished in order to build roads.

Besides, Lopez did much to support the bus-driver Diaz, as he had not only brought the existence of the old Customs’ papers to light. He had also prevented a lot of annoyance with the Law. Nevertheless he was accused by „Renfe“ (the Spanish Railway Company) of having illegally withheld historical documents. Lopez drew up a document, bearing an official seal, stating that the railway had abandoned the papers and left them lying around in the open and this could not be described as theft. At first Diaz, the finder of these papers, refused to hand them over to the Spanish State. He sald, „I request that Spain declares that I found the documents and saved them from being destroyed or going astray. When this has been done, they will be returned immediately”. As a token of his goodwill, Diaz gave the Mayor of Canfranc one of the documents.