History has always been a teacher. Over time, again and again there have been examples for the failure of a futurable and ambitious goal by very small-minded thinking, personal animosity, immense private interests, rivalry or incompetence. Canfranc is a good example for that. The exciting project based on revolutionary, European ideas for that time was condemned to failure by wrong decisions and petty interests.

In 1853, the bank director Juan Bruil from Zaragoza, got the idea to build a train connection via the central Pyrenees as the shortest connection between Madrid and Paris. He submitted the 30-page offer to “Friends of the Country”, a club of very influential employers. At Christmas of the same year two engineers got a special present: They were asked to prepare the first planning of the project. This was the starting point of an endless dispute concerning the best route and the fight of representatives of cities and provinces who wanted to benefit from the planning. It took about 30 years before the government allowed the project in 1882.

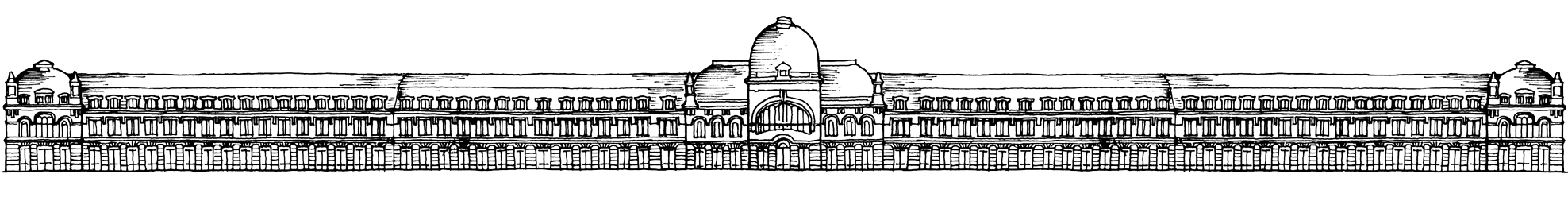

Experts watched the weather 15 years before they came to an agreement about the valley of Aragón and Canfranc as the location of the border station and the Southern end of the tunnel. Technical problems and diplomatic difficulties marked the development of the construction project; repeatedly there were building freezes and delays. In the beginning, the problem of building a tunnel of such length through the Pyrenees was unsolvable. In 1915 the tunnel with a length of 7875 meters was finalized. Through stones, which had been taken from the mountain, the constructors built an artificial plateau on which the huge railway building was raised, a stylistic mixture of classicism and art nouveau.

“The Pyrenees no longer exist”, King Alfonso XIII of Spain supposedly exclaimed proudly when opening the route and the magnificent railway station in the summer of 1928, with the presence of General Primo de Rivera and the President of the French Republic, Gaston Doumergue. After over 70 years of planning and building the project had become reality after all. Of course, the people of the desolate mountain valley hoped to get a small piece of the prosperity and the economic growth which was expected from the nonstop railway road. The luxury brought by the hotel and the expectation of guests coming from all over Europe awakened desires and the wish to be a part of the wealth.

But with the refusal by the Spanish government to adapt its own railway wheel track to the European standard and to electrify the railway road, the seed of failure of the project had already been planted while building the road. Because of this, for each ride a stopover at Canfranc was necessary to switch trains. One side of the building had the Spanish wheel track, the other side had a French wheel track. The length of the trains required a station of immense length. Each passenger had to go through passport control at the station, each piece of luggage through customs, all goods had to be lifted by a crane from one train to the other. Soon it became clear that the loss of time at Canfranc rendered the road unprofitable for carriers. Only 8 years after the opening the Somport-tunnel, which cut the Pyrenees and connected France to Spain, was temporarily closed due to the Spanish Civil War.

After the war the traffic was resumed. During the Second World War Canfranc regained importance: Today we know that ore, which was urgently needed for the production of weapons, was delivered to the German Reich through this road. In return gold as means of payment was transported to the Iberian Peninsula, which on the one hand originated from captured stocks of the European Central Bank, on the other hand from what was obtained through dispossessions and eliminations through the persecution of Jews.

The road also became an important escape path, first for Jews and politically persecuted, for example Max Ernst, who wrote in his biography about his arrival in Canfranc. In our guestbook, you can find an entry from a man who fled with his family through Canfranc at that time. There are distressing reports about the circumstances of the vital attempt to escape the influence of the Nazi dictatorship. In this context I recommend the books of Varian Fry and Lisa Fittko. In times of free travel and free visa within the European Union I cannot imagine those circumstances and they are difficult to understand.

With the occupation of Vichy-France by the German Reich the German military was also present at the railway station of Canfranc. At the same time operations around the station by different secret services increased immensely. The help of the director of the French customs was also documented. He supported persecuted people’s attempts to escape, to go into hiding in Spain, on the way to secure freedom. He also passed on information to the embassies of the Allies in Madrid and was connected with members of the French resistance.

Later on, fleeing Nazis also used this railway line and the tunnel on their road to escape to South America. After the war, having been closed by Franco for a short time, Canfranc reached a certain importance again, e. g. as background of the film “Doktor Schiwago”. The scenes of the railway station were shot there. In 1970, a descending and fully loaded train derailed on the French side, which led to the collapse of the Estanguet railway bridge. That was the end of the international railway traffic.

Since then, the whole construction has been decaying, slowly but surely. The Spanish railway kept their contractual commitment and preserved the functioning.  But the rails with the French wheel track were not used anymore. Since the transportation of goods was also over, the facilities for transhipping were doomed to deterioration. Because of the limited usage of the railway station, there were not enough financial resources for the preservation of the building and so it became constantly worse. When the roof became leaky, rainwater soaked in and destroyed the interior through wetness and frost. As example I am presenting a picture here showing the stairs of the hotel and the conditions in winter. And I thank the friendly Spaniard for having given it to me.

But the rails with the French wheel track were not used anymore. Since the transportation of goods was also over, the facilities for transhipping were doomed to deterioration. Because of the limited usage of the railway station, there were not enough financial resources for the preservation of the building and so it became constantly worse. When the roof became leaky, rainwater soaked in and destroyed the interior through wetness and frost. As example I am presenting a picture here showing the stairs of the hotel and the conditions in winter. And I thank the friendly Spaniard for having given it to me.

When I was in Canfranc for the first time, in 1996, the three-part railcar stopped directly at the station. The engines were kept running for a long time, and there was an unbelievable smell of diesel exhaust gas. At that time there was a real stationmaster wearing a red hat. There was also a post office in the building of the railway station. Additionally, there were accommodations on the first floor of the building, which were used by people with lower income. There were clotheslines at the windows where the clothes fluttered in the slight wind of the Pyrenees.

By now, the post office does not exist anymore, it has migrated to better preserved rooms in the city. The previously closed office of the director of the railway station, which we were allowed to take pictures of in 1997, was destroyed by vandalism by the following year. Soon after that, there was no station master anymore and the railcar was only one-part. Then, a new station platform for the one- part train was built on the side closest to the street. The railway station got fenced and the doors were nailed up with wooden boards. Today, trains run from Zaragoza to Canfranc and back twice a day. In winter, many guests may use it during the ski season. However, in summer, the train is pretty empty, though the route is still spectacular despite its state.

The new start-up of the road is repeatedly talked about. I still remember the words of the EU commissioner, Loyola de Palacio, during the opening of our exhibition in the European Parliament, promising the recommissioning of the route in 2006. That was many years ago, since then, not much has happened, despite all kinds of effort. In the meantime, the old railway line to Bedous has resumed on the French side. But the last piece is missing. And even if it became reality once, the time of the railway station is over, unfortunately. In times of modern technique and changeover points, there will certainly soon be a new stop, placed off the “international railway station of Canfranc”, where you can find enough open areas.

Finally, Canfranc is a memorial for an early pioneering spirit, for visionary ideas and a European idea at a time when nationalism was on the rise. At the same time, it is also a memorial for failure due to narrow horizons, hesitation and rivalries.

© Matthias Maas 2019